What if I told you America’s biggest battles weren’t just fought with guns, but with cotton, taxes, and rage?

Why did a farming crop spark a war that split a nation?

How did angry steel workers in Ohio help send a billionaire to the White House?

And what secret link connects slavery, tariffs, hillbillies, and Trump?

This isn’t your high school history class—it’s the untold story of money, power, and the people caught in between. Keep reading, because once you see the connections, you can’t unsee them.

Table of Contents

TARIFFS AND RIFFS

- The United States ran on two very different engines: an industrial North and a cotton-powered South.

- The North industrialized fast, but it still trailed advanced manufacturers like Britain and had higher production costs.

- To protect local factories from cheaper, well-made European goods, Northerners favored high tariffs.

- The South saw it differently.

- Cotton was the main cash crop, and more than 70% was shipped to Europe.

- High tariffs risked foreign retaliation, which could choke cotton exports while raising import prices—no thanks, said the South.

- So the split was clear: the North feared cheap imports would crush homegrown industry; the South felt it was footing the bill to protect Northern factories.

CHAINS AND GAINS

8. Slavery was another deep divide between North and South.

9. Cotton farming was labor-hungry, and Southern plantations depended on enslaved labor.

10. The North’s growing population and factory economy meant it didn’t rely on slavery the same way.

11. The sharper disagreement early on was over importing enslaved people rather than the existence of slavery itself.

12. Many in the North initially accepted slavery but condemned the brutal slave trade.

13. In 1807, Congress banned the importation of enslaved people.

14. That law didn’t end slavery; it ended the transatlantic import trade.

15. The South agreed, assuming the existing enslaved population would suffice for cotton.

16. That bet aged badly.

17. Cotton turned out to be far more profitable than expected, and production exploded.

COTTON COUNTS, PRICES MOUNT

18. Around 1790, U.S. cotton output was roughly at the thousand-ton level—tiny compared with what came next.

19. By 1820, production had surged to around seventy thousand tons, and by 1860 it was pushing toward nine hundred thousand tons.

20. The American South ended up producing about two-thirds of the world’s cotton.

21. The enslaved population rose fast too—roughly 700,000 in 1790 to about 1.5 million by 1820, and still climbing.

22. Natural increase couldn’t fully match the labor hunger of booming cotton.

23. Basic market math kicked in: when something’s scarce and demand is hot, the price shoots up.

24. The market price of an enslaved person rose from roughly $50 in the late 18th century to hundreds of dollars—often $800 or more by the mid-19th century.

25. As prices climbed, the total “asset value” of enslaved people in the South reached into the billions—on the order of roughly $2 billion—and made up a large slice (around one-fifth) of Southern wealth.

26. Emancipation, in that light, looked to many Southern owners like watching 20% of their property vanish overnight.

RATES AND FATES

27. In 1828, to shelter Northern industry, the United States enacted steep tariffs—often in the mid-40% range.

28. The South erupted, and South Carolina floated secession.

29. A compromise followed.

30. Tariffs would step down gradually to about 20%.

31. But by 1861 the deal was broken; average rates on dutiable goods jumped back into the high 30s and toward the 40s again.

32. On April 12, 1861, the Civil War began.

33. That conflict is known simply as the Civil War.

CAUSES AND CLAUSES

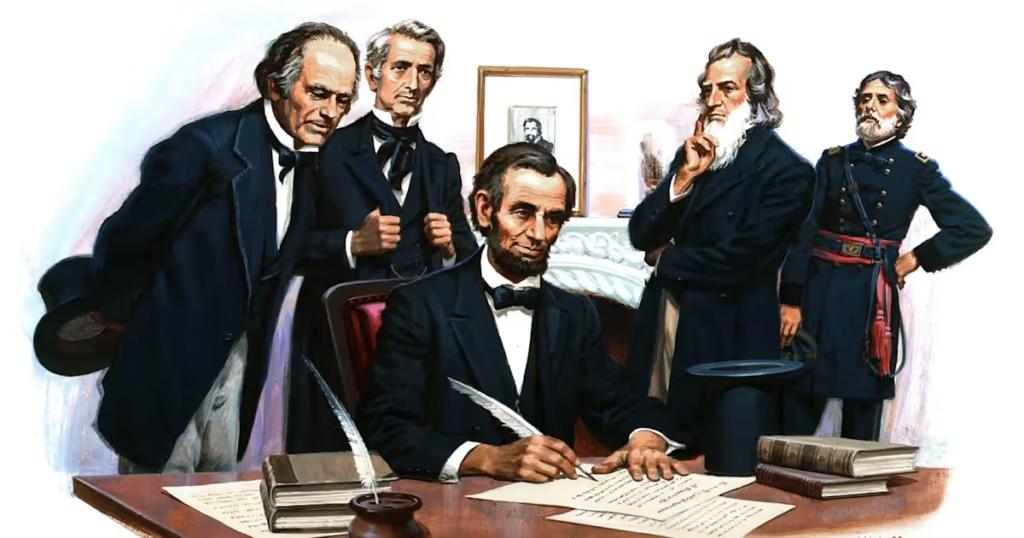

34. Historians read the causes in many ways: tariffs helped spark tensions; slavery—especially its expansion and politics—supplied the defining moral and political clash.

35. Lincoln wasn’t an early, pure-theory abolitionist, and Republicans at first were not unanimously for immediate nationwide abolition.

36. Politics mattered: emancipation would reshape power.

37. Before the war, enslaved people were counted at three-fifths for representation—effectively far from a full vote for Black Americans while empowering slave states.

38. Emancipation meant, in time, real citizenship—one person, one vote.

39. That promised to expand the Republican voter base, including in parts of the South.

40. For Southern elites, losing both wealth and congressional clout was a nonstarter.

41. The South declared independence and went to war.

42. But the North held the stronger hand.

43. The Union had roughly 22 million people to the Confederacy’s about 9 million (including millions enslaved).

44. Industry tilted heavily North: the Union produced the overwhelming share of war supplies—think 90%+ in many categories and about 97% of firearms.

SHOTS, SCOTS, AND TURNING PLOTS

45. There was a snag: many Northern troops weren’t raised around guns.

46. Southerners often were—rural life meant more firearm familiarity.

47. That helped the South notch early battlefield wins.

48. Then the plot turned.

49. Scots-Irish settlers from the Appalachian region joined the Union ranks in large numbers.

50. The Appalachians run like a long backbone along the eastern United States beside the Atlantic.

51. Many Scots-Irish had historic beef with British rule and had settled throughout the uplands.

52. They had a fierce reputation and knew their way around weapons.

53. Think of the rugged, quick-on-the-draw types you see in old Westerns—that vibe.

54. Culturally, they distrusted both Northern elites and Southern slaveholding planters.

55. With a “the side that starts the fight is in the wrong” ethos, many threw in with the Union.

56. Their fighting skill helped tip momentum toward Northern victory.

FREEDOM MEETS FRICTION

57. After Northern victory and emancipation, new tensions surfaced.

58. Some newly freed Black Americans moved into upland areas and towns, competing for jobs.

59. Wages were low and work was scarce, so competition bred resentment.

60. The Ku Klux Klan grew in this climate as well as across the broader South.

61. The Klan’s burning-cross theater drew on an old Scottish “fiery cross” signal; the white hooded costumes were popularized later by novels and film.

62. Many Scots-Irish and other upland whites had little formal schooling and worked as hands in auto plants, steel mills, and heavy industry.

63. They came to be nicknamed “hillbillies.”

64. The term broadened over time to mean poor white working-class folks in struggling Rust Belt towns.

65. When U.S. automakers lost ground to foreign competition and cheap imported steel undercut prices, plants closed—and these workers got hammered.

66. People who once had stable jobs and a middle-class shot were suddenly out of work.

RUST TO BUST TO BALLOTS

67. In June 2016, a book landed.

68. Hillbilly Elegy stayed on bestseller lists for more than a year and hit a nerve nationwide.

69. The author’s hometown, Middletown, Ohio, grew up around Armco/AK Steel, a major steelworks.

70. As cheap imported steel surged, the company’s fortunes fell—and so did workers’ lives.

71. The town slid into drinking, cursing, fighting, and more domestic violence.

72. The author watched a neighbor on unemployment buy a T-bone steak he himself couldn’t afford.

73. He also saw people flipping food-stamp purchases for cash to buy alcohol.

74. The book crystalized anger at welfare abuses (real or perceived) and at the collapse of American manufacturing.

75. That anger channeled into passionate support for Donald Trump’s blunt, straight-ahead message.

76. The Rust Belt had long leaned Democratic.

77. Many blue-collar Democrats became Trump voters.

78. Those flips helped elect him president.

79. For hillbilly voters, simple slogans landed: they wanted action, not jargon.

80. The argument went like this: China eroded U.S. steel and manufacturing—hit back; illegal immigration—secure the border with serious infrastructure.

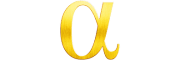

81. In office, Trump made reviving U.S. manufacturing a centerpiece.

82. As he campaigned again, he kept courting those swing-state working-class voters.

83. That’s one reason he chose J.D. Vance—the Hillbilly Elegy author—as his running mate (he is now the Vice President).

ENGINES VS. ELECTRONS

86. Hillbilly jobs have long clustered in auto and heavy manufacturing.

87. Bringing factories back home and raising certain tariffs to protect domestic industry fit that jobs-first lens.

88. That’s also why he moved to phase out federal EV subsidies and credits.

89. Gas cars support vast parts-supplier networks; EVs generally need fewer parts.

90. From a jobs angle, slowing the EV switch while extending the life of gas-car manufacturing can look like buying time for those workers.

Votes and Dollars: The Hidden Currency of Power

Look at the world through the lens of ballots and banknotes, and suddenly everything shifts.

Trump’s tariff wars? Not just trade fights—pure vote math and money muscle.

His pushback on electric cars? Less about tech, more about jobs and who holds the paycheck.

Even Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation wasn’t only a moral mission—it carried the weight of political advantage, boosting Republican votes.

History isn’t just shaped by ideals; it’s written in the language of votes and dollars. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

Discover more from Alphazen Dynamics

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.